Winter stayed a long time in the high Pyrenees last year. The snow lasted on the ground and all wildlife was slow to emerge into the spring sunshine.

We had decided to make an earlyish start to our June expedition only to discover on arrival that our plans might have been better served to have waited an extra week or two. But time, tide and Pyrenean weather wait for no man, so we assembled cheerfully in St. Pierre dels Forçats, high in the mountains, and took local advice on which of the mountain paths and trails to explore.

In the event we were never disappointed, as the views were stunning with high-level snow adding an elegant backdrop, mountain streams gushing with snow melt and all nature readily welcoming the arrival of warmer weather.

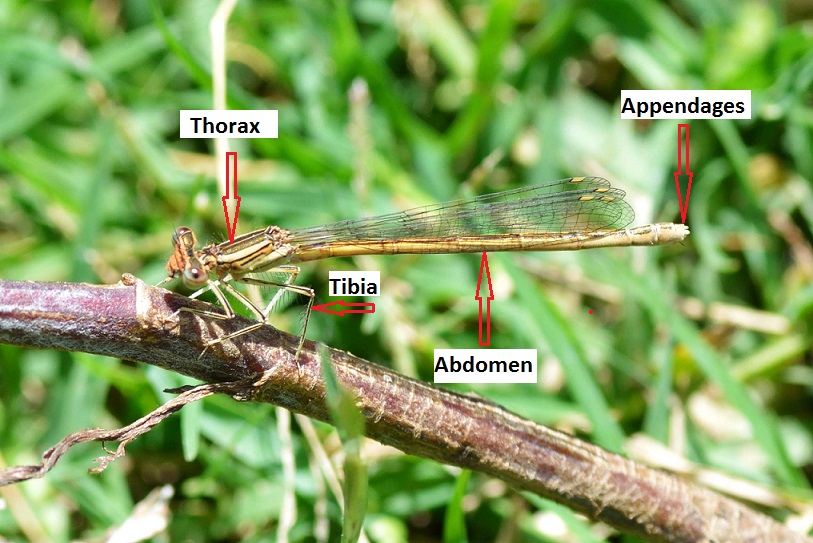

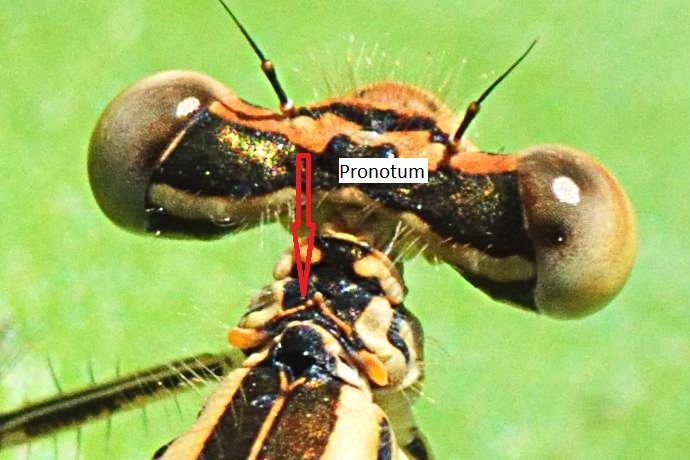

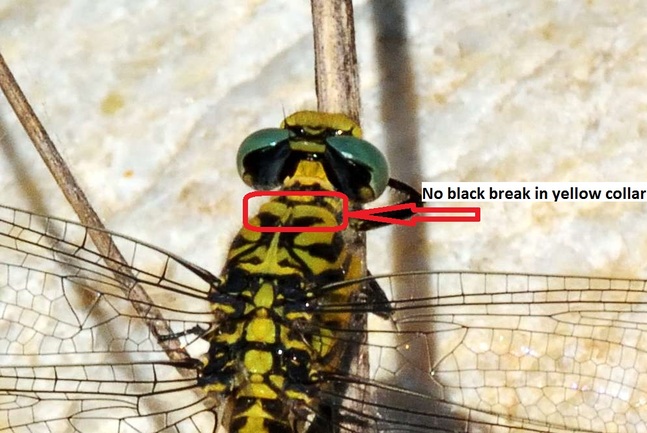

With my specialty being dragonflies, I was somewhat disappointed to see only one species. However, I know they are quite late arrivals, typically waiting for warm sunshine before emerging, and the late snows were not to their liking. This was the dragon I saw, a Broad-bodied Chaser (Libellula depressa)

One of these – a Bright-eyed Ringlet (Erebie oeme) - is very much a high-level butterfly, inhabiting the upper levels of the Pyrenees from near Pau as far east as the Pic du Canigou.

A new blue, Amanda’s Blue (Polyommatus amandus) occupies a habitat that runs along northern Spain, then the Pyrenees, and follows the Mediterranean coast as far as the Alps. It appears to be widespread in Eastern Europe.

Another very pretty specimen was this Adonis Blue (Polyommatus bellargus). To be expected here, as its territory covers most of Europe from Portugal to Turkey; it is absent in all but the south of UK and, curiously, from the southern tip of Italy.

The Eros Blue (Polyommatus eros) was another new one. In France, this high-level insect is only found in the Pyrenees, the Alps and Cantal in the massif central. I think we were lucky to come across it as it usually doesn’t appear until July.

The third new blue was the Mazarine Blue (Cyaniris semiargus), which copes with high altitudes, up to 2000 metres. Extinct in Britain, it has a wide distribution in mainland Europe, from near the Arctic circle down to the Mediterranean.

The fourth and final new one among these tiny jewels was the Turquoise Blue (Plebicula dorylas), whose range extends from northern Spain, across the centre of France and well into Eastern Europe.

This Pearl-bordered Fritillary (Boloria Euphrosyne) insisted on hanging upside down as it nectared on vetch. It has an enormous range covering most of Europe as far north as the Arctic circle.

Finally, there was this Wood White (Leptidea sinapis) which was rather more obliging for my camera. Terrain like the Pyrenees is a perfect habitat, and it is probable that the ones I saw would have over-wintered as pupae.

And, in just that scenario, lies my memory of forgetfulness. Armed with my camera over my shoulder, and knapsack containing telephoto lens, bottles of water, sandwiches and other stuff, I was enjoying a steep walk up the surfaced footpath of the Sègre Gorge walk. After an hour or so I turned to head back, whereupon, to my surprise, I met Ann and Isobel.

I passed a few people coming down and asked each if they had seen the bag. Yes, they said it was beside the path. It took a good 45 minutes of strenuous uphill power-walking before I rounded a bend and saw it – exactly where I had left it. I sent thanks to the gods of the mountains! Then back down again – which seemed to take forever. Ann was walking up to meet me; we heaved a collective sigh of relief and decided that a cold beer was very much the order of the day. And so it was – and particularly delicious too!

Our home for those few days was a traditional timber chalet at the edge of the village where we enjoyed the rural life.